Understanding the Different Types of Miso

Understanding the Different Types of Miso

Miso is a paste made from fermented soybeans with a peanut butter like texture and key ingredient in Japanese cooking. While many associate miso mostly just with soup, there are so many uses beyond that. This is especially true because there are so many kinds of miso.

The base of all miso is soybeans, along with the water, salt, and the koji whose mold facilitates fermentation. The foundation of a koji is a cereal — generally rice, barley, or just pure soybean. (We’ll talk more about that koji in a bit.)

Shiro Miso

Also known as white miso, shiro miso is a bit sweet and less intense.

The difference between white and red miso starts early in the production process. Shiro miso is fermented for the shortest period of time so has the mildest flavor.

In general, shiro miso tends to be used in — and contribute to — more refreshing dishes with its slightly sweet, light taste, while darker miso are more suited for hardier dishes. Shiro miso is great for soups, dressings and marinades.

Aka Miso

While shiro miso is also known as white miso, aka miso is also called red miso.

Soybeans are fermented for a much longer period than shiro miso and also made with a larger amount of soybeans. The result is a more concentrated flavor with a saltier taste and more vivid appearance.

As you could guess, aka miso is used to create bolder, stronger flavors — it’s especially well-suited for hearty winter dishes. Unlike shiro, aka can overpower lighter ingredients so it’s wise to make sure the other components of a dish containing aka miso are able to withstand its boldness. Aka miso is great in stews and to add in marinades.

Awase Miso

After both red and white is a miso that’s not one or the other but a mixture of both. As one could expect, the appearance of awase miso is also in between the other two; it’s a pleasant bronze-y hue and the flavor is also somewhere in the middle of shiro’s refreshing lightness and aka’s assertive taste.

Because of how awase combines the characteristics of both red and white miso, it’s quite versatile and popular. Tip: Mix red and white miso together at home to suit your personal taste.

Dashi Iri

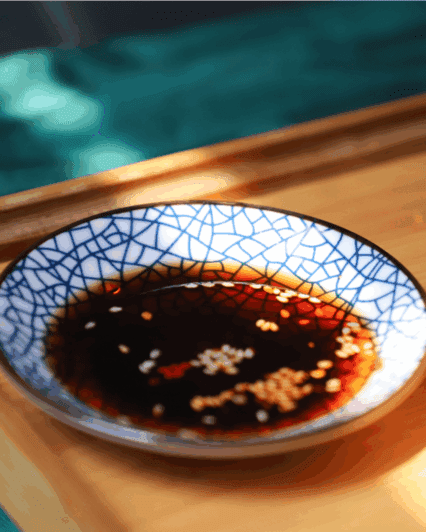

Dashi of course is best known as the umami broth that is the foundation to many Japanese dishes, but it also can be used as an ingredient in miso.

Dashi iri isn’t itself one type of miso — rather it’s a variation on other types wherein dashi is added during production. This causes the final product to have similar qualities it would originally have — for example, a dashi iri white miso will still be relatively mild and a bit sweet — but with an added undertone of umami.

These kinds of miso thus have an added earthy complexity beyond the flavors of their non-dashi-containing counterparts.

Hatcho Miso

While most misos are made primarily from soybeans, they usually also include a secondary grain component. This, however, is not the case with hatcho, which is pure fermented soybean miso: Just soybeans, water, and salt.

Hatcho has a red undertone and is extremely dark, thick, and strong. This is due to both the concentration of soybeans relative to other ingredients, undiluted by another cereal, and because it’s aged for up to three years.

Mugi Miso

Considered in some ways a subset of white miso, mugi miso is made with a combination of fermented soybeans and barley as the other grain.

Although mugi’s production process includes a relatively long period of fermentation, its flavor actually isn’t as strong as that aging would suggest; the taste is still rather mild, and the barley gives off an accompanying earthy fullness.

Koji

Last is koji, which isn’t miso but rather a key ingredient. It’s the culture that makes miso possible, whether made of rice, barley, or just pure soybean. Read more about koji here. Without koji, the mixture of soybeans, salt, and water wouldn’t ferment into miso. It’s in the koji where the accompanying grain comes into play, too; in mugi, for example, the barley is included as barley koji.

It’s not just used in miso but is also beloved in Japan for its use in loads of other fermented foods like soy sauce, mirin, and sake.

Another fun fact about koji is that it plays a big part in miso being popular in marinades, since the enzymes that result from it help break down and tenderize meat.

One of the many great things about miso is that there are so many varieties that each bring something special and different to the table. Whether making lighter dishes, hardy foods, or earthy, complex dishes, miso brings a flavorful depth that makes everything delicious.